Adding executables to your PATH for fun

Adding executables to your PATH is fun, easy, and a great way to learn about how your machine works.

This pattern is especially useful for long commands that you need to run frequently.

Learning how to add executables to your PATH will help you understand how libraries like pyenv use the shim design pattern to seamlessly switch between Python versions.

While we're learning about this design pattern, we'll also review how your machine uses the PATH and where executables are stored on our system.

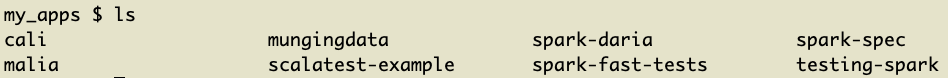

Building a more useful file listing command

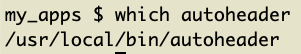

The ls command outputs the files and folders in the current directory.

The ls output is more useful when it is run with flags so the output shows hidden directories and file sizes.

It's common to create a ll command that runs ls -ahlF. You don't want to always type ls -ahlF every time you do a file listing.

It's best to use a ~/.bash_profile alias for something simple like this, as described in this answer. We'll create an executable and add it to our path for learning purposes. This will set us up nicely for a more complicated example.

Let's start by creating a ~/.cali/ll file. We'll put our executables in the ~/.cali directory, following this design pattern.

Open the ll file with a text editor and add ls -ahlF.

We can run the ll script with bash ~/.cali/ll, but we can't run ~/.cali/ll yet because the file isn't an executable.

Let's make the ll file an executable: chmod +x ~/.cali/ll.

We want to be able to run ll from the command line, just like any other Terminal command. We can run ~/.cali/ll, but we want to be able to simply run ll from any directory, similar to ls.

Let's append ~/.cali to our PATH environment variable.

Add this code to the ~/.bash_profile file:

We can reload the bash profile with source ~/.bash_profile and then run ll from the command line.

Understanding PATH

The PATH environment variable is an ordered list of directories that contain executables.

You can view the contents of your PATH by running echo $PATH. It'll return something like this: /usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/sbin:/sbin:/Users/matthewpowers/.cali.

Each directory is separated by a colon. It's easier to view them as a list:

- /usr/local/bin

- /usr/bin

- /bin

- /usr/sbin

- /sbin

- /Users/matthewpowers/.cali

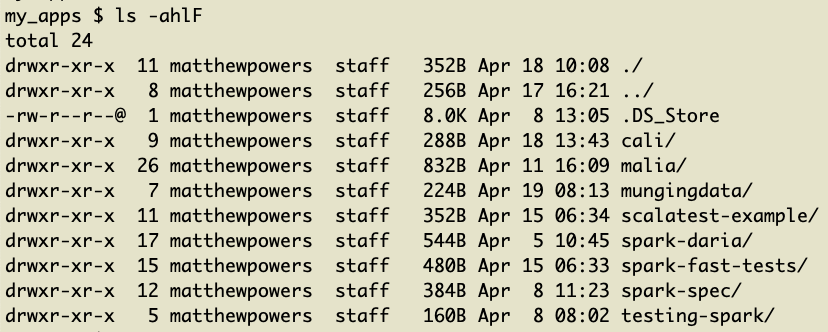

Here are some of the files contained in /usr/local/bin on my machine.

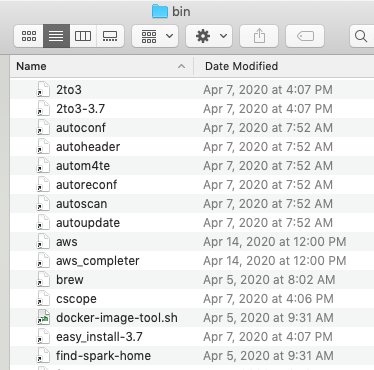

We can type which autoheader to find where this executable file is stored on my system.

We can type which ls to see that the ls executable is stored in the /bin directory.

When ls ~/Documents is run, your computer will start by looking for an ls executable in the /usr/local/bin directory. It won't find one, so it'll look in /usr/bin. It wont find one there either, so it'll look in /bin. It'll find the executable in /bin, so it'll stop looking and use the /bin/ls executable.

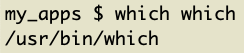

We can even type which which to see that the which executable is stored in /usr/bin:

This is too much fun!!!

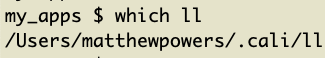

Let's type which ll and see where the ll executable is stored:

Of course, ll is in the ~/.cali directory - that's where we put it!

Adding s3_ll

The AWS CLI offers this command to see the size of a S3 bucket: aws s3 ls --summarize --human-readable --recursive s3://bucket-name/directory.

This command is too long to remember. Let's create an executable that takes a single argument. We want s3_ll my_bucket/some_folder to run aws s3 ls --summarize --human-readable --recursive s3://my_bucket/some_folder.

Let's create the ~/.cali/s3_ll file.

Open the file and add this code: aws s3 ls --summarize --human-readable --recursive s3://$1

The $1 is how we pass the argument from the Terminal command to the shell script. In the s3_ll s3_ll my_bucket/some_folder, s3_ll is the command and my_bucket/some_folder is the argument. $1 is how we access the argument in the shell script.

Shim design pattern

We appended the .cali directory to our path - we put the directory at the end of the PATH environment variable.

The shim design pattern depends on prepending a directory to our path to intercept commands.

pyenv and rbenv use the shim design pattern to allow users to seamlessly switch between Python and Ruby versions.

Read this post to learn more about the shim design pattern.

Next steps

Adding executables to your path is fun and useful.

It teaches you about how your system executes commands.

Customizing your environment is great, as long as the customizations are documented and stored in a version controlled repo. You should be able to easily replicate your custom setup on a different machine. Take a look at cali for an example of customizations that can be easily transitioned to a new machine.